"I have followed multiple divergent paths in my life. A constant has been that I have worked on behalf of artists to help get recognition for their work—whether interviewing and photographing quiltmakers, curating exhibitions, creating documentaries about artists, and now working on public art projects. The public art realm has been hugely satisfying because of the permanence of these projects and the impact they have on people’s lives.” —Caroline Lerch

Caroline Lerch grew up in New Orleans, where it’s said music is everywhere. It certainly was in Caroline’s house—her grandfather was a jazz musician and pianist who could be heard on the local radio every morning on the "Pinky Vidacovich and the Dawnbusters" show, and her mother, Haydée Lafaye Ellis, played guitar and upright bass in a band with a regular gig in the French Quarter. Haydée also painted and acted in local theater productions—all the while being a conventional PTA mom, married to a civil engineer.

Caroline Lerch grew up in New Orleans, where it’s said music is everywhere. It certainly was in Caroline’s house—her grandfather was a jazz musician and pianist who could be heard on the local radio every morning on the "Pinky Vidacovich and the Dawnbusters" show, and her mother, Haydée Lafaye Ellis, played guitar and upright bass in a band with a regular gig in the French Quarter. Haydée also painted and acted in local theater productions—all the while being a conventional PTA mom, married to a civil engineer.

She managed to embody all of these things at the same time,

Caroline said. Thinking back on my upbringing has made me realize that it probably influenced my own path and career development. I felt like I could be many things at once.

While pursuing a graduate school degree in art history with a focus on folk art at the University of Mississippi, Caroline developed a passion for African American folk quits. Following in the path of famed folklorist (and eventual Director of the National Endowment of the Humanities) Dr. William Ferris, she did fieldwork in the Mississippi Delta, documenting quiltmakers and artists and filming interviews. This was well before the blockbuster The Quilts of Gee’s Bend

show at the Whitney Museum of American Art brought attention to the genre.

There has been a lot of scholarship and research on these quilts, about their improvisational quality that some people compare to jazz. Resembling abstract paintings, they are asymmetrical and vibrant, with a creative and resourceful use of materials. They are quite different than quilts in the Anglo tradition, which are focused on precision, symmetry, and more subdued colors,

Caroline said. I wanted to document the quiltmakers I met before they disappeared, and to bring attention to their work. I organized exhibitions in Oxford, Mississippi and New Orleans during that time.

Caroline moved to New York for an internship at the American Folk Art Museum, and within a couple of years—in her mid-20s—co-founded the groundbreaking Outsider Art Fair, which showcased the work of self-taught artists and artists living with neurodiversity (autism and other developmental disabilities, schizophrenia, and Tourette's syndrome, for example). It was a huge success and is still being produced today in New York and Paris. She served as its Director for 12 years. The fair really introduced this field to thousands of visitors—including curators, members of the press, and collectors. Many artists’ careers were launched or boosted as a result and a great deal of them ended up in in museum collections.

Wearing all kind of creative hats now, just like her mom, Caroline moved on to open her own gallery in the East Village, Kerrigan Campbell art + projects, for emerging contemporary artists, and was the Photo Editor for a hip-hop magazine, XXL. She also worked for renowned documentarian Michael Blackwood, and has Associate Producer credit on films including Alvaro Siza: Transforming Reality,

A Day with Zaha Hadid,

and Gerhard Richter: 4 Decades,

among others. She organized an exhibition, fundraiser, and lecture series at Cooper Union with curator and gallerist Margaret Bodell. It was called Mind Matters, and featured Temple Grandin, Oliver Sacks, and Andrew Solomon for the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, and culminated in a fundraiser concert with Winton Marsalis. With the tintype photographer John Coffer—who revived the wet-plate collodion photography process before artists such as Chuck Close and Sally Mann—she organized a photo shoot in the closed New York City Hall subway stop with him and Robert Polidori for New Yorker magazine.

After 15 years in New York, now married and a mother to a young daughter, Caroline moved to Berlin, Germany, and worked from there for the American Folk Art Museum, organizing and directing their art fair fundraiser, The American Antiques Show (TAAS). In 2011, she moved back to the States after a job offer from the Art Fair Company to start, produce, and manage its latest art fair endeavor, the Metropolitan Show, featuring contemporary and historic material. A few years later, she became the Deputy Director of Prospect:3, the international art biennial in New Orleans, which brought her fully into the public art realm.

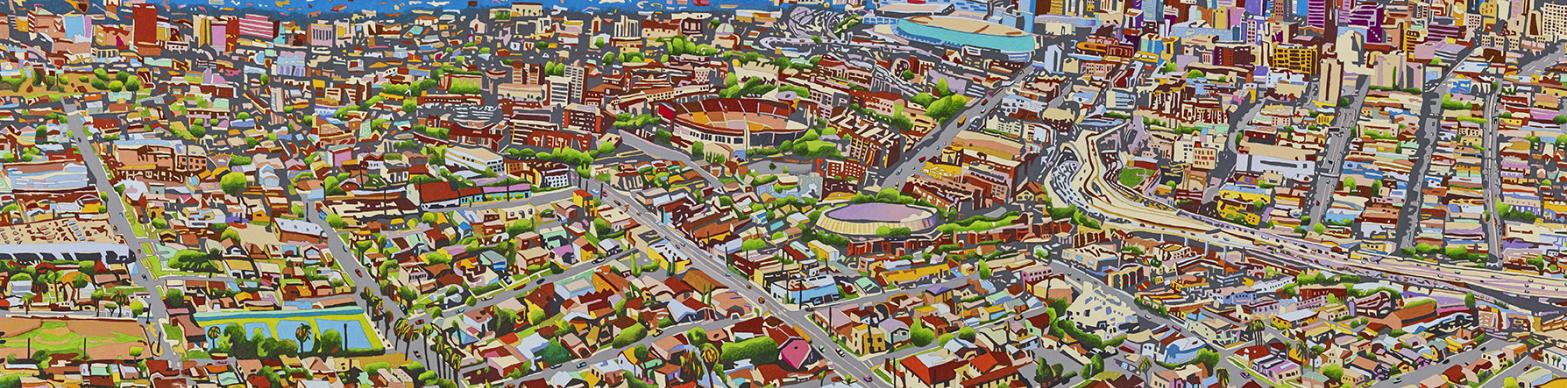

When Caroline started traveling to Los Angeles to work with artists there, she became interested in a move to the West Coast. In 2016, she was offered, and took, a Project Manager job at the then Los Angeles County Arts Commission where she manages civic art projects within LA County’s Civic Art Policy, which allocates 1% of the design and construction costs of County capital projects for civic art.

Caroline has been in Los Angeles for almost six years and loves it. There’s so much going on here in terms of the art scene. There are so many interesting galleries, and a really supportive community of artists,

she said.

Since starting with the Arts Commission, Caroline has worked on projects such as Christine Nguyen’s photo-based mural and hanging sculpture at the Sheila Kuehl Family Wellness Center, Amir Fallah’s fused and stained glass project at the new Department of Mental Health and Workforce Development, Aging and Community Services headquarters in Koreatown, Olalekan Jeyifous’ murals at the Developing Opportunities Offering Reentry Solutions Center (DOORS), Fabian DeBora’s artist in residency centering arts-based healing in the reentry process at the DOORS Center, and Rebeca Mendez’s mosaic tile mural at the Greater Whittier Regional Aquatic Center.

Just like my mother,

Caroline said. I have followed multiple divergent paths in my life. A constant has been that I have worked on behalf of artists to help get recognition for their work—whether interviewing and photographing quiltmakers, curating exhibitions, creating documentaries about artists, and now working on public art projects. The public art realm has been hugely satisfying because of the permanence of these projects and the impact they have on people’s lives.